A German U-Boat Sinks the Algonquin and Bombs America Into World War I

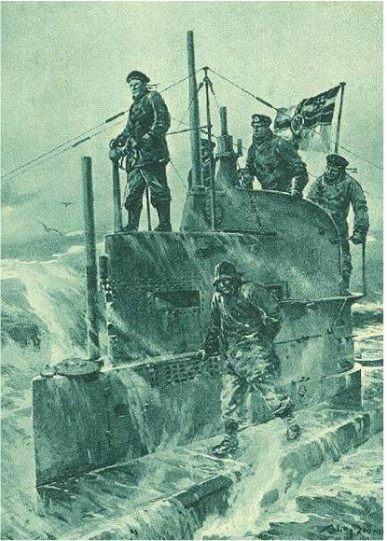

German submarine, World War I

Willy Stower

German submarine, World War I

Willy Stower

The American steamship Algonquin was one of the last casualties of Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that brought American into World War I.

For the United States, the first four months of 1917 were a swift slide down a slippery slope into World War I. In January 1917, Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that it had abandoned in 1915 after SMU-20 torpedoed the Lusitania. Germany’s new policy targeted all ships trading with Britain, including the ships of neutral countries like the United States.

German Foreign Secretary Zimmerman Sends a TelegramIn February 1917, the British intercepted a telegram that came from Arthur Zimmerman, the German Foreign Secretary, to the German Ambassador to Mexico and gave a copy to the American ambassador. Secretary Zimmerman proposed that in case of a war with the United States, Germany and Mexico would become allies. Germany would bankroll Mexico’s war with the United States and when Germany and Mexico won, Mexico would reclaim her lost territories of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico.

The American ambassador reported the contents of the Zimmerman Telegram and American indignation against Germany escalated. The American public grew more incensed when German submarines sank four United States merchant ships and 15 Americans died.

The Steamship Algonquin Leaves New York in February, 1917

The steamship Algonquin was one of the first American merchant ships to leave the United States after Germany announced her submarine blockade. On February 20, 1917, she sailed from New York bound for London carrying foodstuffs. The Algonquin didn’t carry any munitions, she flew the American flag and the flag was also painted on her side. Her cargo was valued at $1,700,000.

Built in 1888 at Glasgow, Scotland, the Algonquin was a single screw steamer of 1,086 tons gross, 245 feet long, and 40 feet of beam. She operated between New York and St. Johns, New Brunswick under Canadian ownership and British registry from 1900 to 1916. The Algonquin was transferred to the American flag in December 1916, when the American Star Line purchased her.

Departing from New York City, the Algonquin safely crossed the Atlantic and had reached a point about 65 miles off of Bishops Rock, a small rock at the westernmost tip of the Isle of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall, when she enllcountered a German U-boat. The U-boat opened fire on the Algonquin from a distance of 4,000 yards, firing about twenty shells. These failed to sink the steamer, so men from the submarine carrying bombs boarded the Algonquin and detonated the bombs to sink her.

The crew of 26 men, eleven of them Americans, put off in small boats and after 27 hours of strenuous rowing landed safely at Penzance on the Cornish coast on March 14, 1917.

Captain Nordberg Tells His StoryCaptain A. Nordberg and his crew arrived in Plymouth, England, on March 15, 1917. He gave eyewitness testimony about the German sinking of the Algonquin. According to Captain Nordberg, on Monday morning, March 12, 1917, he stood on the bridge just after daylight on the mate’s watch and he and the mate spotted a submarine that they estimated was about three miles away. The captain saw the flash of a gun and a shell fell short of the Algonquin. “There was no warning. I stopped the engines and then went full speed astern, indicating this by three blasts on the whistle. The submarine kept on firing, the fourth shot throwing a column of water up which drenched me and the man at the wheel. It was a close call.”

Captain Nordberg and Crew Take to the LifeboatsAfter four of the shots that the Germans had fired hit the Algonquin, the crew took to the boats. According to Captain Nordberg, the submarine approached and with only its periscope showing, circled the steamer several times. The submarine surfaced and some of the Germans boarded the ship and placed bombs aft. The bombs exploded and the Algonquin sank within a quarter of an hour.

Captain Nordberg said, “I appealed to the submarine commander for a tow toward land in view of the roughness of the weather, but the German commander gruffly replied. “No, I am too busy.”

The crew of the Algonquin pulled away in the life boats. None of them were injured by shell fire, but suffered from exposure. All of their personal effects and the ships papers were lost.

The London Times Comments

A story in the March 15, 1917, London Times commented on the sinking of the Algonquin. “London is past expecting anything but the worst from German submarine commanders, but nevertheless reports of some of the details of the sinking of the American steamer Algonquin aroused indignation here today.”

According to the survivors, the crew of the submarine which they variously identified as the U-38 and U-39, seemed determined to demolish the lifeboats with their gunfire. They boarded the Algonquin, hauled down the American flag and exploded bombs in the ship’s hold.

The U boat crew laughed at the Algonquin's crew and refused to tow the ship’s lifeboats nearer shore. The crew of the Algonquin was almost exhausted from 27 hours of strenuous rowing when a British ship rescued them.

One of the Algonquin's Owners Weighs In

On March 14, 1917, John Stephanidis of New York, one of the owners of the Algonquin, said that he expected to go to Washington and discuss the sinking of the steamer with President Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing.

President Wilson Appears Before CongressLess than a month later, at 8:30 on the evening of April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appeared before a joint session of Congress asking for a declaration of war against Germany, largely because of its unrestricted submarine warfare. On April 4, 1917, Congress granted Wilson’s request and the United States was at war with Germany.

References

Gibson, R.H. and Prendergast, Maurice, The German Submarine War, 1914-1918, Periscope Publishing Ltd., 2002.

Halpern, Paul G., A Naval History of World War I, Routledge, 1995.

Herwig, Holger H., “Total Rhetoric, Limited War: Germany’s U-Boat Campaign, 1917-1918:, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, The Centre for Military and Strategic Studies (Spring, 1998)

For the United States, the first four months of 1917 were a swift slide down a slippery slope into World War I. In January 1917, Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that it had abandoned in 1915 after SMU-20 torpedoed the Lusitania. Germany’s new policy targeted all ships trading with Britain, including the ships of neutral countries like the United States.

German Foreign Secretary Zimmerman Sends a TelegramIn February 1917, the British intercepted a telegram that came from Arthur Zimmerman, the German Foreign Secretary, to the German Ambassador to Mexico and gave a copy to the American ambassador. Secretary Zimmerman proposed that in case of a war with the United States, Germany and Mexico would become allies. Germany would bankroll Mexico’s war with the United States and when Germany and Mexico won, Mexico would reclaim her lost territories of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico.

The American ambassador reported the contents of the Zimmerman Telegram and American indignation against Germany escalated. The American public grew more incensed when German submarines sank four United States merchant ships and 15 Americans died.

The Steamship Algonquin Leaves New York in February, 1917

The steamship Algonquin was one of the first American merchant ships to leave the United States after Germany announced her submarine blockade. On February 20, 1917, she sailed from New York bound for London carrying foodstuffs. The Algonquin didn’t carry any munitions, she flew the American flag and the flag was also painted on her side. Her cargo was valued at $1,700,000.

Built in 1888 at Glasgow, Scotland, the Algonquin was a single screw steamer of 1,086 tons gross, 245 feet long, and 40 feet of beam. She operated between New York and St. Johns, New Brunswick under Canadian ownership and British registry from 1900 to 1916. The Algonquin was transferred to the American flag in December 1916, when the American Star Line purchased her.

Departing from New York City, the Algonquin safely crossed the Atlantic and had reached a point about 65 miles off of Bishops Rock, a small rock at the westernmost tip of the Isle of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall, when she enllcountered a German U-boat. The U-boat opened fire on the Algonquin from a distance of 4,000 yards, firing about twenty shells. These failed to sink the steamer, so men from the submarine carrying bombs boarded the Algonquin and detonated the bombs to sink her.

The crew of 26 men, eleven of them Americans, put off in small boats and after 27 hours of strenuous rowing landed safely at Penzance on the Cornish coast on March 14, 1917.

Captain Nordberg Tells His StoryCaptain A. Nordberg and his crew arrived in Plymouth, England, on March 15, 1917. He gave eyewitness testimony about the German sinking of the Algonquin. According to Captain Nordberg, on Monday morning, March 12, 1917, he stood on the bridge just after daylight on the mate’s watch and he and the mate spotted a submarine that they estimated was about three miles away. The captain saw the flash of a gun and a shell fell short of the Algonquin. “There was no warning. I stopped the engines and then went full speed astern, indicating this by three blasts on the whistle. The submarine kept on firing, the fourth shot throwing a column of water up which drenched me and the man at the wheel. It was a close call.”

Captain Nordberg and Crew Take to the LifeboatsAfter four of the shots that the Germans had fired hit the Algonquin, the crew took to the boats. According to Captain Nordberg, the submarine approached and with only its periscope showing, circled the steamer several times. The submarine surfaced and some of the Germans boarded the ship and placed bombs aft. The bombs exploded and the Algonquin sank within a quarter of an hour.

Captain Nordberg said, “I appealed to the submarine commander for a tow toward land in view of the roughness of the weather, but the German commander gruffly replied. “No, I am too busy.”

The crew of the Algonquin pulled away in the life boats. None of them were injured by shell fire, but suffered from exposure. All of their personal effects and the ships papers were lost.

The London Times Comments

A story in the March 15, 1917, London Times commented on the sinking of the Algonquin. “London is past expecting anything but the worst from German submarine commanders, but nevertheless reports of some of the details of the sinking of the American steamer Algonquin aroused indignation here today.”

According to the survivors, the crew of the submarine which they variously identified as the U-38 and U-39, seemed determined to demolish the lifeboats with their gunfire. They boarded the Algonquin, hauled down the American flag and exploded bombs in the ship’s hold.

The U boat crew laughed at the Algonquin's crew and refused to tow the ship’s lifeboats nearer shore. The crew of the Algonquin was almost exhausted from 27 hours of strenuous rowing when a British ship rescued them.

One of the Algonquin's Owners Weighs In

On March 14, 1917, John Stephanidis of New York, one of the owners of the Algonquin, said that he expected to go to Washington and discuss the sinking of the steamer with President Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing.

President Wilson Appears Before CongressLess than a month later, at 8:30 on the evening of April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appeared before a joint session of Congress asking for a declaration of war against Germany, largely because of its unrestricted submarine warfare. On April 4, 1917, Congress granted Wilson’s request and the United States was at war with Germany.

References

Gibson, R.H. and Prendergast, Maurice, The German Submarine War, 1914-1918, Periscope Publishing Ltd., 2002.

Halpern, Paul G., A Naval History of World War I, Routledge, 1995.

Herwig, Holger H., “Total Rhetoric, Limited War: Germany’s U-Boat Campaign, 1917-1918:, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, The Centre for Military and Strategic Studies (Spring, 1998)