The Steamship Pulaski's Passengers Survive Her Sinking and Fall in Love

In 1838, the steamship Pulaski sank off the coast of North Carolina when her boiler exploded, but two of her passengers discoveredsurvival skills and each other.

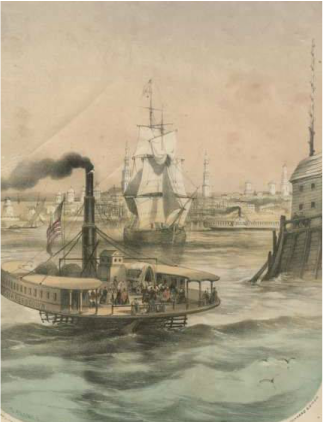

Steamship boilers often exploded, fatally scalding passengers and crew, and furnishing maritime history with countless disaster stories. The sinking of the steamship Pulaski off the coast of North Carolina on Wednesday and Thursday, June 13- 14, 1838, marked one of the first explosions of a coastal steamship, but with a romantic twist if a Brooklyn Eagle account of two survivors is more than a legend.

The Pulaski Is Advertised As The State of the Art Titanic of Its Time

The Savannah and Charleston Steam Packet Company built the Pulaski to safely and speedily carry freight and passengers from Savannah, Georgia, to Baltimore, Maryland with pick up stops in Charleston, South Carolina. Advertisements in newspapers of the day touted the marvels of the Pulaski’s 225 horse power engine and her copper boilers as well as her spacious accommodations for passengers.

// According to the Wilmington Advertiser newspaper story, on Wednesday, June 13, 1838, the Pulaski with Captain Dubois at the helm and a crew of 37 seamen and a contingent of passengers, left Savannah, Georgia, bound for Baltimore, Maryland. After boarding about 65 more passengers in Charleston, South Carolina, Captain Dubois set the Pulaski’s course for Baltimore. The Pulaski steamed to about thirty miles off the North Carolina coast through a dark night and moderate weather.

The Pulaski’s Starboard Boiler Blows Up

Around ten o’clock the night of Wednesday, June 13, 1838, the Pulaski’s starboard boiler suddenly exploded, shattering the starboard side of her mid section and dislodging the bulkhead between the boilers and the forward cabins. The explosion swept some passengers into the sea and scalded others to death. First Mate S. Hibbert, on watch at the forecastle, unsuccessfully searched for Captain Dubois who was never seen again. Panicky passengers, most of them wearing their night clothes, sought refuge on the promenade deck. The bow of the Pulaski rose out of the water and eventually she ripped apart.

Passengers clung to furniture and pieces of wreckage. As the Pulaski sank, the crew lowered four life boats, with two capsizing while the other two filled with frantic passengers. Forty five minutes after the boiler explosion, about half of the Pulaski’s passengers had drowned, or were scalded to death or crushed by the falling masts.

Some Passengers Survived the Pulaski’s Boiler Explosion

The people in the two lifeboats searched for survivors most of the night, and with daybreak, rowed toward the North Carolina shore. One of the lifeboats capsized in sight of land, but the other landed safely after fighting crashing breakers. Other survivors still floated in the Atlantic Ocean. Major Health and second captain Pearson built a makeshift raft by lashing wreckage together with ropes and welcomed 22 people aboard. The survivors clung to the raft an endless Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, suffering from hunger and thirst and exposure to the relentless waves. Four more survivors who had clung to wreckage climbed aboard the raft on Saturday morning.

Hope revived the exhausted spirits and bodies of the survivors when they spotted the Carolina coast line, but the fierce wind swept away their hopes as quickly as it swept the raft back to sea. After a stormy weekend, Monday morning dawned calm and clear and Monday afternoon brought sightings of four ships, but no rescue. Tuesday morning brought another sighting of sails on the horizon. A schooner bound for Wilmington, North Carolina, The Henry Camerdon, rescued the 26 survivors and eventually picked up four more survivors clinging to a smaller piece of wreckage.

A Pulaski Disaster Love Story, Legend or Both

According to the Brooklyn Eagle story, a Mr. Ridge from New Orleans and a Miss Onslow from a Southern state, were two of the passengers who were picked up on Saturday morning about fifty miles from land. When the Pulaski’s boiler exploded, Mr. Ridge had given himself up for lost when he spied a coil of small rope. He grabbed it and lashed a piece of an old sail, a couple of settees, and a small empty cask together with it and launched himself and his raft upon the cold Atlantic. Sighing with relief, he looked down into the water and saw a woman struggling in the water at the side of his raft. He dove into the water, swam to her, grabbed her, and hoisted them both onto his makeshift raft. The woman he rescued turned out to be Miss Onslow, the young lady that he had admired from afar earlier in the voyage.

Miss Onslow didn’t have much faith in their raft. "You will have to let me go to save yourself," she said.

He answered, "We live or we die together."

Soon one of the small lifeboats floated toward them, and although it already had a heavy load of people, Mr. Ridge implored them to take Miss Onslow aboard. She refused to leave him. Together they suffered scorching heat and the lack of a morsel to eat or a cooling drink of water. To the despair of Mr. Ridge and Miss Onslow, their small raft eventually drifted away from the two lifeboats. At daylight they could see nothing but the sky and vast meadows of rolling water, but then they began to focus their attention on each other. She admired his fearlessness, his resourcefulness in saving their lives, and his concern for her despite the fact they were strangers. She confessed to deep feelings of gratitude and the beginnings of stronger feelings toward him.

He admired her good sense, her fortitude, her presence of mind, and especially her willingness to share his fate. Against the backdrop of the Atlantic Ocean, endless sky, and uncertain future they became engaged.

When they were finally rescued, Miss Onslow and Mr. Ridge were sunburned, starved, and exhausted, but happy to be alive.

The Happily Ever After of the Pulaski

In the closing months of 1838, an inquiry into the explosion of the Pulaski found that the engineers had improperly operated the boilers on the Pulaski and caused the explosion. Gradually, public opinion caused Congress to pass regulations that governed steamer inspections, but these preventive actions came too late for the 100 passengers who had perished in the Pulaski explosion.

After Mr. Ridge and Miss Onslow were rescued, he told her that duty and his conscience forced him to make a confession. The sinking of the Pulaski caused him to lose his entire $25,000 net worth. He told her that he was in poverty "to his very lips." He offered to release her from their engagement if she chose to leave him.

Bursting into tears at the thought of separating from him, Miss Onslow asked him if he thought that the lack of money could change the importance of what they had survived together. He assured her that he would repeatedly endure the same trials and tribulations for her and expressed his happiness at her willingness to marry him even though he didn’t have a penny. Their engagement survived and they set a wedding date.

Then she told him that she stood to inherit an estate worth $200,000.

References

Coleman, Kenneth. A History of Georgia. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

Howeden, Joseph Russell. The Boy’s Book of Steamships. Grant Richards 1923.

Jackson, George Gibbard. The Splendid Book of Steamships. Low, 2010.