The CSS Alabama's Canon is Home in Alabama

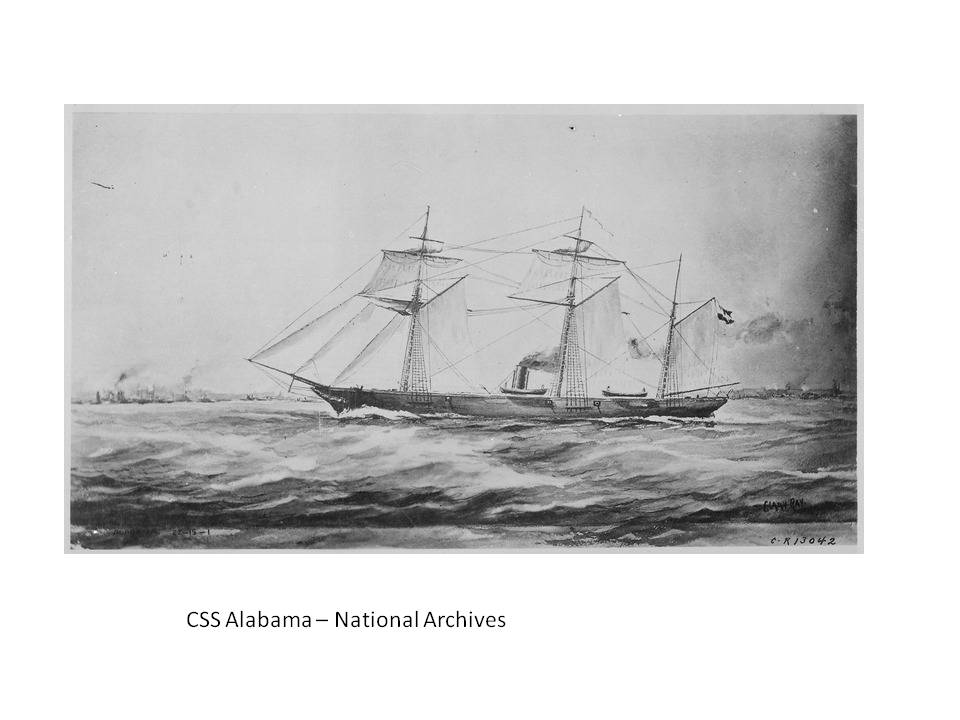

The Tallahassee, the Alabama, which was a commerce raider, and many of the Confederate blockade runners were built in English shipyards

On April 19,1861, a week after the Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln ordered a blockade of Southern ports. He and his advisors believed that the blockade would prevent supplies from entering the Southern states, and also prevent cotton from leaving the South’s main ports of New Orleans, Louisiana, Charleston, South Carolina, and Mobile, Alabama. During the first two years of the blockade, over two-thirds of the ships making the attempt managed to negotiate the blockade.

The Confederate Congress established the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed forces on February 21, 1861. The Confederate Navy was charged with protecting Southern harbors and coastlines from invasion , attacking merchant ships, and breaking the Union Blockade.

The Confederacy managed to maintain a high percentage of successful blockade running because Confederate ships were custom built, with low silhouettes, light draft, and high speeds. Many of these custom built ships, equipped with both steam an sail, were built in English shipyards because the Confederacy had few shipbuilding facilities of its own.

The Union Pressures Great Britain

The United States government pressured England to stop the building of ironclads and warships for the Confederacy. On May 13, 1861, Queen Victoria issued a "Proclamation of Neutrality" that prohibited the sale of ships of war. Ships could enter British waters but couldn’t change or improve their equipment while they remained in British waters.

Probably the most famous English built blockade runners were the Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah, but the Tallahassee managed to hold her own in this illustrious company.

Most of the ship’s crews were British seamen who were attracted by the high wages and possibilities of prize money to be collected after the war’s end if the Confederacy won.

English Shipyards Supply the Confederate Navy

British built ships helped the South successfully navigate the blockade. Millwall, below London, was located on the western side of the Isle of Dogs on the north bank of the Thames near Greenwich. Napier Yard, the shipyard leased by Messrs. J. Scott Russell and Company was the birthplace of the Tallahassee, the SS Great Eastern and many other ships.

People with strong political, financial, and emotional connections to the Confederate States of America lived in the area around Liverpool and Lancashire. John Townley in Merseyside Connections with the American Civil War said that "more Confederate flags fluttered above Liverpool than over Richmond."

Officer Bullock Shops for the Confederacy in Liverpool

Confederate naval officer James Bulloch came to Liverpool on June 4, 1861, with orders from the Confederate Navy to buy or build six steam vessels to use against the Union. He also had orders to buy arms for the cruisers and run them through the blockade. Fraser, Trenholm and Co., foreign bankers to the Confederacy assisted him.

James Bulloch signed his first contract with Fawcett & Preston Engineers in Liverpool and WC Miller and Son Ship Builders to build the CSS Florida , finished in 1861. He signed the second contract in July 1861 with Laird Brothers who had a shipyard near Liverpool to build the Enrica.

On June 23, 1862, American Minister to London Charles Francis Adams, protested that the Laird firm had built the Enrica and other vessels under suspicious circumstances. The British authorities didn’t find enough evidence of the violation of neutrality and despite repeated efforts of the United States government, the building of the Enrica went forward.

The Alabama Scores Victories for the Confederacy

The Enrica sailed for Anglesey for trials on July 29, 1862, without arms and carrying a party of ladies and custom officials, but they were soon transferred to another ship and taken back to land. The Enrica sailed off for the Azores to take on armaments and ammunition and begin its working life as the CSS Alabama. The majority of the Alabama’s crew came from Liverpool and most of the crew voluntarily joined the Confederate Navy.

On August 13, 1862, Captain Raphael Semmes took command of the Alabama and from then until June 1864, worked effectively for the Confederate Navy. Captain Semmes and the Alabama captured and burned 55 Union merchant ships worth $4,500,00 and bonded ten others valued at $562,000.

The Kearsarge Sinks the Alabama and England Pays the "Alabama Claim"

On August 19, 1864, the CSS Alabamamet the USS Kearsarge off Cherbourg, France and thousands of French citizens watched as the Kearsarge sank the Alabama in the spectacular battle off the French coast. The steam yacht Deerhound, also built at Lairds and owned by Englishman John Lancaster, saved a number of the crew of the Alabama and the people of Southampton gave them a hero’s welcome.

The United States Government demanded that the British Government pay compensation for the damage that the Confederate ships caused . The case was called the "Alabama Claim," because the Alabama had caused the most damage and with the Florida and Shenandoah, had accounted for half of the total number of Union vessels captured. In 1873,the British government settled the claim for four million American dollars because it had permitted the Confederate Government to purchase the ships in England and allowed them to use British ports.

The Alabama and her fellow raiders had heavily damaged the United States Merchant Marine and it didn’t recover after the war. The British merchant fleet remained the world’s largest for the next 70 years. The Alabama lay at the bottom of the English Channel for 146 years until a French ship rediscovered her.

CSS Alabama Cannon's Home is in Alabama at the Museum of Mobile

One of the cannons from the CSS Alabama is now on display at the Museum of Mobile in Mobile, Alabama. It arrived at the Museum on Tuesday, June 15, 2010. The Alabama’s cannon is the central exhibit in the 700 foot square exhibit gallery, joining the collection of other artifacts recovered from the Alabama that are on loan from the United States Navy.

The cannon is black in color, approximately 10 feet long and weighs2 ½ tons. It is one of the three recovered of the original six of that size. One is at the Navy Yard in Washington and the other is in Charleston, South Carolina.

According to Mobile lawyer Robert Edington ,President of the CSS Alabama Association, French and American divers recovered this cannon from the wreck of the CSS Alabama in 2003. Since then the underwater archaeologists at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina, preserved the cannon until it was transported to Mobile.

The cannon’s original gun carriage had completely rotted away after 140 years underwater and it had to be replaced. Experienced craftsmen from Mobile Public Buildings built a replacement gun carriage. "The expertise of these artisans cannot go without note. The original plans for the gun carriage, dated May 1862, were located in England and copied exactly," Robert Edington said.

The Alabama Was a Premier Blockade Runner

The CSS Alabama was one of the premier Confederate blockade runners built in the Laird Brothers shipyard near Liverpool, England. From 1862 until 1864, the Alabama claimed more than 60 prizes valued at approximately six million dollars and made heavy inroads into United States merchant shipping. The Union's USS Kearsarge sank the Alabama in a fierce battle off the coast of Cherbourg, France on June 19, 1864.

The Alabama is Rediscovered

On October 30, 1984, the French Navy mine hunter Circe discovered a wreck in approximately 200 feet of water off Cherbourg, France. French Navy Commander Max Guerout later confirmed that the wreck was the Alabama. Despite the fact that the Alabama lies within French territorial waters, the United States government claimed the Alabama as a spoil of war.

In October 1989, the United States and France signed an agreement acknowledging that the CSS Alabama is an important heritage of both countries and established a joint French-American Scientific Committee to direct archaeological investigations of the wreck.

Exploring and Excavating the Alabama

In 1995, the CSS Alabama Association and the Naval Historical Center signed an official agreement granting the CSS Alabama Association permission to investigate the Alabama remains. In 1999, the CSS Alabama Association, based in Mobile, Alabama, joined the French organization to actively support exploring the Alabama.

The French exploration team recovered about 200 artifacts from the CSS Alabama in the 1990s. The French and the American joint exploration teams recovered about 200 more. They turned most of the artifacts over to the United States Department of the Navy for restoration. There have been no dives on the wreck site since 2005 because of a lack of funding.

A Confederate Sailor is Also Discovered

The remains of a Confederate sailor were discovered in 2003, encrusted on the bottom of the cannon. American archaeologists raised the cannon during the summer of 2002, and the cannon and the remains were sent to the Warren Lasch Conservation Laboratory in North Charleston, South Carolina.

In a Mobile Register story, Shea McLean, the Museum of Mobile's curator of collections that he found the remains of the sailor sometime in 2003, on the underside of the cannon as if it had crushed the sailor. He said that the remains were eventually sent to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii and DNA samples were taken. He said that there is no doubt that the remains were of a Confederate sailor and he hoped to use the DNA to trace the sailor's descendants through a list of the crew.

According to the Mobile Register, the Confederate sailor was buried on July 28, 2007, in Confederate Rest in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile, with approximately 1,100 Confederate soldiers. Raphael Semmes, the commanding officer of the CSS Alabama, spent the last years of his life in Mobile and is buried in the Catholic Cemetery there.

References

Foster, Kevin J. The Search for Speed Under Steam: The Design of Blockade Running Steamships, 1861-1865. East Carolina: MA Thesis, 1991.

Hearn, Chester G. Gray. Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union's High Seas Commerce. Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1996.

Hollett, David. The Alabama Affair: The British Shipyards Conspiracy in the American Civil War. Wilmslow: Sigma Press, 1993.

Hoole, W. Stanley (ed.). Confederate Foreign Agent: The European Diary of Major Edward C. Anderson. Alabama: Confederate Publishing Company, 1976.

Semmes, Admiral Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War between the States. Secaucus: The Blue & Grey Press, 1987.

On April 19,1861, a week after the Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln ordered a blockade of Southern ports. He and his advisors believed that the blockade would prevent supplies from entering the Southern states, and also prevent cotton from leaving the South’s main ports of New Orleans, Louisiana, Charleston, South Carolina, and Mobile, Alabama. During the first two years of the blockade, over two-thirds of the ships making the attempt managed to negotiate the blockade.

The Confederate Congress established the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed forces on February 21, 1861. The Confederate Navy was charged with protecting Southern harbors and coastlines from invasion , attacking merchant ships, and breaking the Union Blockade.

The Confederacy managed to maintain a high percentage of successful blockade running because Confederate ships were custom built, with low silhouettes, light draft, and high speeds. Many of these custom built ships, equipped with both steam an sail, were built in English shipyards because the Confederacy had few shipbuilding facilities of its own.

The Union Pressures Great Britain

The United States government pressured England to stop the building of ironclads and warships for the Confederacy. On May 13, 1861, Queen Victoria issued a "Proclamation of Neutrality" that prohibited the sale of ships of war. Ships could enter British waters but couldn’t change or improve their equipment while they remained in British waters.

Probably the most famous English built blockade runners were the Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah, but the Tallahassee managed to hold her own in this illustrious company.

Most of the ship’s crews were British seamen who were attracted by the high wages and possibilities of prize money to be collected after the war’s end if the Confederacy won.

English Shipyards Supply the Confederate Navy

British built ships helped the South successfully navigate the blockade. Millwall, below London, was located on the western side of the Isle of Dogs on the north bank of the Thames near Greenwich. Napier Yard, the shipyard leased by Messrs. J. Scott Russell and Company was the birthplace of the Tallahassee, the SS Great Eastern and many other ships.

People with strong political, financial, and emotional connections to the Confederate States of America lived in the area around Liverpool and Lancashire. John Townley in Merseyside Connections with the American Civil War said that "more Confederate flags fluttered above Liverpool than over Richmond."

Officer Bullock Shops for the Confederacy in Liverpool

Confederate naval officer James Bulloch came to Liverpool on June 4, 1861, with orders from the Confederate Navy to buy or build six steam vessels to use against the Union. He also had orders to buy arms for the cruisers and run them through the blockade. Fraser, Trenholm and Co., foreign bankers to the Confederacy assisted him.

James Bulloch signed his first contract with Fawcett & Preston Engineers in Liverpool and WC Miller and Son Ship Builders to build the CSS Florida , finished in 1861. He signed the second contract in July 1861 with Laird Brothers who had a shipyard near Liverpool to build the Enrica.

On June 23, 1862, American Minister to London Charles Francis Adams, protested that the Laird firm had built the Enrica and other vessels under suspicious circumstances. The British authorities didn’t find enough evidence of the violation of neutrality and despite repeated efforts of the United States government, the building of the Enrica went forward.

The Alabama Scores Victories for the Confederacy

The Enrica sailed for Anglesey for trials on July 29, 1862, without arms and carrying a party of ladies and custom officials, but they were soon transferred to another ship and taken back to land. The Enrica sailed off for the Azores to take on armaments and ammunition and begin its working life as the CSS Alabama. The majority of the Alabama’s crew came from Liverpool and most of the crew voluntarily joined the Confederate Navy.

On August 13, 1862, Captain Raphael Semmes took command of the Alabama and from then until June 1864, worked effectively for the Confederate Navy. Captain Semmes and the Alabama captured and burned 55 Union merchant ships worth $4,500,00 and bonded ten others valued at $562,000.

The Kearsarge Sinks the Alabama and England Pays the "Alabama Claim"

On August 19, 1864, the CSS Alabamamet the USS Kearsarge off Cherbourg, France and thousands of French citizens watched as the Kearsarge sank the Alabama in the spectacular battle off the French coast. The steam yacht Deerhound, also built at Lairds and owned by Englishman John Lancaster, saved a number of the crew of the Alabama and the people of Southampton gave them a hero’s welcome.

The United States Government demanded that the British Government pay compensation for the damage that the Confederate ships caused . The case was called the "Alabama Claim," because the Alabama had caused the most damage and with the Florida and Shenandoah, had accounted for half of the total number of Union vessels captured. In 1873,the British government settled the claim for four million American dollars because it had permitted the Confederate Government to purchase the ships in England and allowed them to use British ports.

The Alabama and her fellow raiders had heavily damaged the United States Merchant Marine and it didn’t recover after the war. The British merchant fleet remained the world’s largest for the next 70 years. The Alabama lay at the bottom of the English Channel for 146 years until a French ship rediscovered her.

CSS Alabama Cannon's Home is in Alabama at the Museum of Mobile

One of the cannons from the CSS Alabama is now on display at the Museum of Mobile in Mobile, Alabama. It arrived at the Museum on Tuesday, June 15, 2010. The Alabama’s cannon is the central exhibit in the 700 foot square exhibit gallery, joining the collection of other artifacts recovered from the Alabama that are on loan from the United States Navy.

The cannon is black in color, approximately 10 feet long and weighs2 ½ tons. It is one of the three recovered of the original six of that size. One is at the Navy Yard in Washington and the other is in Charleston, South Carolina.

According to Mobile lawyer Robert Edington ,President of the CSS Alabama Association, French and American divers recovered this cannon from the wreck of the CSS Alabama in 2003. Since then the underwater archaeologists at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina, preserved the cannon until it was transported to Mobile.

The cannon’s original gun carriage had completely rotted away after 140 years underwater and it had to be replaced. Experienced craftsmen from Mobile Public Buildings built a replacement gun carriage. "The expertise of these artisans cannot go without note. The original plans for the gun carriage, dated May 1862, were located in England and copied exactly," Robert Edington said.

The Alabama Was a Premier Blockade Runner

The CSS Alabama was one of the premier Confederate blockade runners built in the Laird Brothers shipyard near Liverpool, England. From 1862 until 1864, the Alabama claimed more than 60 prizes valued at approximately six million dollars and made heavy inroads into United States merchant shipping. The Union's USS Kearsarge sank the Alabama in a fierce battle off the coast of Cherbourg, France on June 19, 1864.

The Alabama is Rediscovered

On October 30, 1984, the French Navy mine hunter Circe discovered a wreck in approximately 200 feet of water off Cherbourg, France. French Navy Commander Max Guerout later confirmed that the wreck was the Alabama. Despite the fact that the Alabama lies within French territorial waters, the United States government claimed the Alabama as a spoil of war.

In October 1989, the United States and France signed an agreement acknowledging that the CSS Alabama is an important heritage of both countries and established a joint French-American Scientific Committee to direct archaeological investigations of the wreck.

Exploring and Excavating the Alabama

In 1995, the CSS Alabama Association and the Naval Historical Center signed an official agreement granting the CSS Alabama Association permission to investigate the Alabama remains. In 1999, the CSS Alabama Association, based in Mobile, Alabama, joined the French organization to actively support exploring the Alabama.

The French exploration team recovered about 200 artifacts from the CSS Alabama in the 1990s. The French and the American joint exploration teams recovered about 200 more. They turned most of the artifacts over to the United States Department of the Navy for restoration. There have been no dives on the wreck site since 2005 because of a lack of funding.

A Confederate Sailor is Also Discovered

The remains of a Confederate sailor were discovered in 2003, encrusted on the bottom of the cannon. American archaeologists raised the cannon during the summer of 2002, and the cannon and the remains were sent to the Warren Lasch Conservation Laboratory in North Charleston, South Carolina.

In a Mobile Register story, Shea McLean, the Museum of Mobile's curator of collections that he found the remains of the sailor sometime in 2003, on the underside of the cannon as if it had crushed the sailor. He said that the remains were eventually sent to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii and DNA samples were taken. He said that there is no doubt that the remains were of a Confederate sailor and he hoped to use the DNA to trace the sailor's descendants through a list of the crew.

According to the Mobile Register, the Confederate sailor was buried on July 28, 2007, in Confederate Rest in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile, with approximately 1,100 Confederate soldiers. Raphael Semmes, the commanding officer of the CSS Alabama, spent the last years of his life in Mobile and is buried in the Catholic Cemetery there.

References

Foster, Kevin J. The Search for Speed Under Steam: The Design of Blockade Running Steamships, 1861-1865. East Carolina: MA Thesis, 1991.

Hearn, Chester G. Gray. Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union's High Seas Commerce. Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1996.

Hollett, David. The Alabama Affair: The British Shipyards Conspiracy in the American Civil War. Wilmslow: Sigma Press, 1993.

Hoole, W. Stanley (ed.). Confederate Foreign Agent: The European Diary of Major Edward C. Anderson. Alabama: Confederate Publishing Company, 1976.

Semmes, Admiral Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War between the States. Secaucus: The Blue & Grey Press, 1987.