"Father Put Me in the Boat -" The Story of the Northfleet

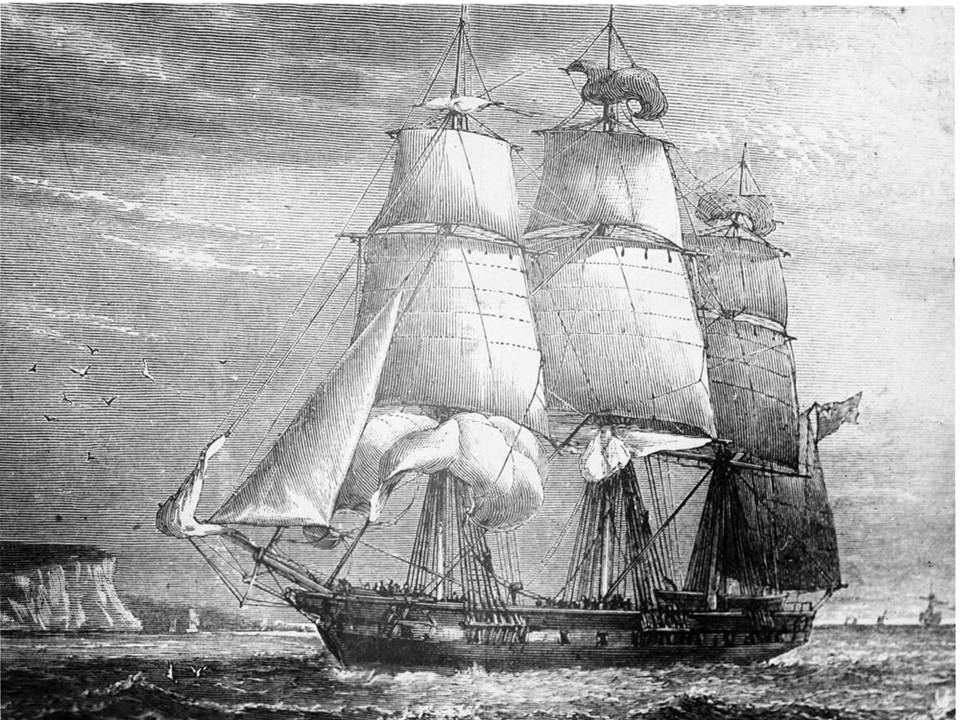

The Northfleet - Wikimedia Commons

The Northfleet - Wikimedia Commons

Much to his disappointment, Captain Thomas Oates couldn’t make his scheduled January 1873 voyage on the Northfleet, a three masted barque which he had commanded for five years, because the Solicitor for the Crown had subpoenaed him to testify in an upcoming criminal trial. Thanking Providence that he had an able officer to take his place, Captain Oates appointed his friend and trusted Chief Officer Edward Knowles to sail the Northfleet from England to Tasmania. Very soon, Captain Oates would thank Providence that he hadn’t been able to make the Northfleet’s voyage.

An Honorable Twenty Years of Sailing

The 951 ton Northfleet was a Blackwall Frigate, one of the three masted full rigged ships built between the late 1830s and the mid 1870s that were originally intended to replace the British East Indiaman in the India, Cape of Good Hope, and China trade. From the 1850s, the Blackwell Frigates were also engaged in the trade between England, Australia, and New Zealand. Built in 1853 in Northfleet Kent and named for her birthplace, the Northfleet spent most of her sailing career plying between England, Australia, India, and China.

In his book Notes by Way of a Sailor’s Life, Arthur E. Knight, who said that he had sailed with the Northfleet for years, revealed some of her early history when he said that she voyaged from China to San Francisco and back to London before she carried troops for the Crimean War. Then for many years she ran between London and China carrying tea. He said that the Northfleet never made a voyage without someone being drowned from her. This January 1873 voyage would prove to be no exception.

The Northfleet’s Last Voyage

In 1872, John Patton Jr. of London owned the Northfleet when she was chartered to carry laborers and their families, 340 tons of iron rails, and 240 tons of other equipment to Hobart, the most populous and capital city of the Australian island state of Tasmania where they would build a railroad line.

There were 379 people on board the Northfleet including the pilot of the tug Landon Trinity, 34 crew members, three cabin passengers and the assisted emigrants headed for new lives in Tasmania. Assisted emigrants were people who could only afford passage to Australia and arrived in Australia and Tasmania with the help of assisted immigration schemes from the United Kingdom and other countries. The assisted emigrants on this voyage were made up of 248 men, 42 women and 52 children.

John Sturgeon, 23, his wife Lucy, 22, and their seven-month old daughter Harriet were on their way to a new life in Tasmania and John Taplin, 44, and his wife Caroline, 43, and daughters, Sarah 13, Caroline, 12, and Maria Taplin, 10, also left London on the Northfleet. John had signed up to work on the Tasmanian Railroad.

Cabin passengers were Mrs. Knowles, the captain’s wife, and Samuel Frederick Brand. The Knowles had been married for just six weeks and Mrs. Knowles agreed to take her first sea voyage to keep her husband company. Besides Mrs. Knowles, two other ordinary cabin passengers also were onboard. Samuel Frederick Brand had accepted a position on the railroad contractor’s staff and although the Australian newspaper the Rockingham Bulletin listed the other cabin passenger as a Mr. Gross, he didn’t appear on the list of the passengers lost or the passengers saved.

The Northfleet Reaches Dungeness

Virtually all accounts of the Northfleet and the Murillo, the Spanish steamer that rammed her, told different versions of the events of the night of January 22, 1873, and several recorded different casualty figures. A book called The Loss of the Northfleet published by in 1873 by Waterlow & Sons, London, featured the testimony of the surviving crew and passengers taken under oath and at inquests. According to Boatswain John Easter in his testimony to the Receiver of Wrecks G.B. Raggett on January 25, 1873, the Northfleet was in excellent condition and classed in Lloyd’s List as A 1 from 1867 to 1873.

Under English Maritime law of the 1870s, a ship’s master had to enter an accounting of a ship’s disaster within 48 hours of the ship entering port, an action called “Noting a Protest.” Afterward, the details of the event were taken from the ship’s log and collected in a document called an “Extended Protest.” The master and the principal members of the crew were sworn to the truth of the events before a notary and this document enforced the groundwork for any claims or compensation for damages. Boatswain John Easter, the sole surviving officer of the Northfleet, testified before Notary William H. Payn in Dover on January 24, 1873.

On January 13, 1873, the Northfleet left London about 11 o’clock in the morning and the tug Landon Trinity pulled her down the Thames River to Gravesend, a town in northwest Kent on the south bank of the Thames River to begin her long voyage to Tasmania. Arriving in Gravesend at 4 o’clock the same day, she was moored to a buoy and remained there until 6 o’clock in the morning of January 17, 1873. The weather turned stormy and the Northfleet stopped at various ports along the English Channel.

The Landon Trinity’s pilot George Brack recommended to Captain Knowles that he anchor the Northfleet and on the night of January 22, she stood at anchor about two or three miles off Dungeness. Some witnesses later said at the inquest that at least 300 boats were anchored at Dungeness that night because of the bad weather. Boatswain Easter testified that the Northfleet rode with her head towards Dungeness light. This Dungeness light was almost certainly lighthouse number three which had been built in 1792 and not the present Old Lighthouse built in 1901.

A Mysterious Steamer Strikes and Slips Away

Darkness covered the English Channel as snugly as the blankets covered the sleeping passengers, but the ships officers swore that bright riding lights illuminated the Northfleet. The crew of the Landon Trinity that had towed the Northfleet reported that at some point after midnight a steamer came under the point to anchor. The tugboat crew watched the steamer moving around for some time and then suddenly a loud crash shattered the peaceful night. From below the Boatswain Easter heard the Watch shouting, “What steamer is that? Where are you coming to?”

Hurrying up on deck, Boatswain Easter discovered that a steamer had struck the Northfleet on the starboard side just before the main hatchway. The Boatswain and the Watch hailed the steamer several times, but no one answered and the steamer backed astern and quickly chugged out of sight.

Landon Trinity tug Pilot George Brack’s testimony differed a little from Boatswain John Easter’s version of the story. George Brack said that he was sitting down in the saloon when he heard the watch cry, “Pilot, pilot come out!” He jumped up, but before he could reach the deck the boat vibrated with a jarring crash. As soon as he came on deck he saw a steamer backing out from the starboard amidships and he also noted that the Northfleet’s riding lights were burning brightly.

George Brack also cried, “What ship is this?” but the ship backed clear of the Northfleet. The noise and impact of the crash brought everyone on deck and Pilot Brack ordered the ship’s carpenter to get the pumps going and then he went below to determine how much damage the ship had sustained. He discovered that the Northfleet was stove amidships and water washed into the ship. He and Captain Knowles conferred and they sent blue distress signals at once, and fired distress rockets.

Only two of the seven lifeboats were launched. According to a Rockingham Bulletin story, Captain Knowles brought his wife to one of the departing boats, placed her in it and said to Boatswain John Easter who had already gotten into the boat, “Here is a charge for you, bo’sen; take care of her and the rest, and God bless you!” He clasped his wife’s hands and told her goodbye, saying, “I shall never see you again!”

Tug Pilot Brack testified that the passengers were terrified because they realized that the ship was sinking, but Captain Knowles acted with great calm and deliberation, ordering the life boats lowered and only women and children into the boats. A group of men rushed toward the quarter boats, cut away the port quarter boat and rowed away from the ship and then he saw the starboard boat full of people pull away from the sinking Northfleet.

Other versions of the story say that Captain Knowles used his pistols to try to prevent men from getting into the two lifeboats instead of the women and children and he shot a man in the knee who refused to obey his orders. The Northfleet sank in less than thirty minutes and everyone went down with her except the people who were clinging to the rigging. Captain Edward Knowles went down with the Northfleet, still trying to rescue passengers.

According to the Rockingham Bulletin story, the boat carrying Mrs. Knowles hailed the steamer tug City of London which had been anchored, but responded to the blue lights and rockets. Captain Kingston picked up the thirty people in the boat and in the hope of rescuing other people he steamed around for three quarters of an hour searching the sea for other victims. An account in the Sydney Morning Herald said that a steam tug, the City of London, anchored nearby rescued 75 of the passengers and 10 of the crew and took them to the Sailor’s Home in Dover. Another source said that the City of London, the lugger Mary, the Princess, and a pilot cutter took off several people but no other ship offered assistance, mostly because they didn’t realize that the Northfleet was in trouble until she sank.

“…Those in Peril on the Sea…”

The night that the Northfleet sank, John Taplin and his wife and daughters were asleep in their berths when the sound of the collision woke them and they all rushed on deck. John Taplin threw Maria into the lifeboat and tried, but failed, to get the rest of his family into the boat. John Sturgeon threw his wife Lucy and baby Harriet into the life boat and clambered in with them. The boat with Mrs.Knowles, Mrs. Sturgeon, baby Harriet, Maria Taplin and thirty men tossed about in the English Channel until finally another ship rescued its passengers and took them to the Sailor’s Home in Dover. Mrs. Knowles volunteered to accompany Maria Taplin to London. The newspapers printed stories about Maria and the death of her mother, father, and sisters, and many people offered to adopt her. Then her two married sisters in Holloway sent telegrams informing her rescuers that Maria was their sister and she must come to live with them and Maria went to live with her sisters.

Arthur Knight noted in his memoir that the Knowles were newlyweds and that when Queen Victoria heard the plight of Mrs. Knowles she sympathized with her and awarded her a pension of fifty pounds a year as long as she remained a widow. Three years after the Northfleet sank, Mrs. Knowles married Captain Cawes of the ship Coriolanus and when the Coriolanus came to Hankow to load tea, Arthur Knight met Mrs. Cawes “who had been saved from my old ship which I had sailed for years.”

The death toll of the Northfleet added up to tragic totals. Of the three cabin passengers only the wife of Captain Knowles was saved. Of the steerage passengers, 177 men were lost and 71 saved. Of the women, there were 41 lost and 1 saved, and of children between one and twelve, 43 were lost and 1, Maria Taplin, saved. The infant toll included 7 lost and one, Harriet Sturgeon, saved. Of the crew including the tug boat pilot, 23 were lost and 11 saved.

Alexander Gloack, Chief Officer, had agreed to take a friend’s place on the Northfleet. Captain Thomas Oates had telegraphed Alexander Gloack at his home in North Scotland and given him an hour to come to the Northfleet and take the place of Chief Officer Edward Knowles so that Knowles could serve as captain on the January 1873 voyage. He joined the ship at Gravesend and died while trying to maintain order striving to carry out his captain’s order: “Clear away the remaining boats.”

A steady, industrious, thrifty man, Alexander Stephens, the carpenter, had made two previous voyages on the Northfleet, and had married a young widow just before Christmas. With his loss, she became a widow for the second time at age 24.

G.M. Blyth, second officer, steady and trustworthy, had served on the Northfleet for 18 months. He left a wife and mother to mourn his untimely death.

John Rinaldo, a well educated Swede, had signed up for the Northfleet’s voyage as a sail maker, but because of his even tempered, honest, and trustworthy disposition he had been promoted to the position of store keeper.

John Easter the Boatswain, and the Pilot George Brack were among the crew that survived as well as Robert Humphries, third cook.

The Inquiries Began

An inquest was held in the town hall at Lydd situated on the Romney Marsh and the most southerly village in Kent, on Saturday afternoon, January 25, 1873, over the body of cabin passenger Samuel Frederick Brand. With Thomas Finn acting as ex-officio coroner, a witness testified that he recognized Samuel Brand’s body. Captain Thomas Oates of the Northfleet testified and at that point Wollaston Knocker, a solicitor from Dover, entered the room and said that he represented the owners of the screw steamer Murillo, asked that he be heard, and requested permission to cross examine the witnesses. He was granted permission.

The funeral of Samuel Frederick Brand, the only cabin passenger whose body was recovered, was held on Saturday January 25 at New Romney after his body had been transported there from Lydd the previous evening. People attending his funeral included his father surgeon Dr. Brand, John Brand, a brother, Captain Thomas Oates of the Northfleet, and W.D. Walker, justice of the peace and a sub agent for Lloyds. The Reverend R. Smith, vicar of St. Nicholas Church, officiated over the burial of Samuel Frederick Brand in a grave under a yew tree in the churchyard. From his grave the spars of the Northfleet were just visible above the sea.

The Spanish Steamer Murillo

Accounts differed greatly as to when investigators discovered that the mysterious steamer that smashed into the Northfleet was the Spanish ship Murillo, Captain Berrute, master. Testimony at the hearing held in Dover two days after the sinking of the Northfleet, stated that a representative of the owners of the Murillo attended the hearing and requested permission to interview witnesses. Other accounts say that it took several months to identify the Murillo and several years to hold her accountable for ramming the Northfleet and leaving her crippled in the water.

The Rockingham Bulletin story said that an eye witness described the offending ship as a two funneled schooner-rigged steamer, but he could not add any more details because the night was so dark. He said that no one on board spoke, although loud shouts from the Northfleet must have made her crew well aware of the terrible danger that existed. He said that the Murillo “backed” for two or three minutes, and then, steamed rapidly away and was soon out of sight.

In his memoirs, Arthur Knight said that the steamer that had run down the Northfleet had been twice arrested, but nothing definite could be proved until two years later when one of her officers who lay dying confessed that the Murillo had run down the Northfleet. Another account said that the Murillo’s crew covered her name with a sheet to keep her from being identified, because they had kept an inadequate lookout.

Just eight days after the sinking The New York Times identified the Murillo as the culprit in a story dated London, January 31, 1873. The story reported that the Murillo had arrived safely at Cadiz despite rumors that she too had foundered and the Lloyd’s agent at Cadiz confirmed that the Murillo had indeed rammed the emigrant ship Northfleet off Dungeness Lighthouse on the night of January 22, 1873. The Murillo did not sustain any damage, and she did not stay to assist the passengers on the Northfleet or inform any other vessels that the Northfleet needed assistance.

The Murillo had been bound for Lisbon, Portugal, with a cargo, but upon arriving there her officials discovered that she could not land because Portugal had an extradition treaty with Great Britain which would have required that the Murillo’s officers be surrendered and subjected to the charges brought against them. The Murillo put to sea again and made her way to Cadiz, Spain, where she landed without fear of arrest because Spain and Great Britain did not have an extradition treaty.

A story in the Wellington Independent dated April 23, 1873 reported that the High Court of Admiralty in England had acted on a claim of the Northfleet owners against the owners of the Murillo to recover damages for the loss of the Northfleet in a collision off Dungeness. The claim was for 14,000 pounds or about 21,000 dollars. The Northfleet owners had previously brought suit against the Murillo for 15,000 pounds or 22,000 dollars, but it was changed to a suit to be brought against the owners instead of the ship. The usual course of action in such cases was to arrest a vessel, and require bail to be given to answer the claim before the ship was released. In this suit the proceedings were against the owners “in personum” as it was termed and they were called upon to appear.

On September 22, 1873, eight months after the Murillo rammed the Northfleet, British authorities arrested the Murillo off of Dover. A Court of Admiralty condemned her to be sold and severely censured her officers.

Remembering the Northfleet

Most of the bodies of the victims who were recovered were unrecognizable and they were laid to rest under memorial stones in St. Thomas’ Churchyard, Winchelsea and at churches in New Romney, Capel-le-Ferne, St. Margaret’s-at-Cliff near Dover, and Lydd, Kent. A memorial at the Church of All Saints in Lydd reads: In memory of William Norman, passenger in the “Northfleet” drowned (23) January 1873 aged 21 years, also five others unknown.

A ballad called “The Wreck of the Northfleet” or “Father Put Me in the Boat,” commemorates the story of the Northfleet and without mentioning her name tells Maria Taplin’s story. The Northfleet is sinking and a little girl on deck does not want to fall into the cold dark sea, so she pleads, “father put me in the boat.”

The ballad describes the desperate scenes around Maria and her father tries to save her mother and two sisters, but he succeeds only in saving her. The last verse of the ballad says:

Although the child was brought to shore,

Her parents and her sisters sleep

Together with three hundred more,

Within the bosom of the deep;

In years to come long may that child

His mercy and his goodness note

Who heard her on that night so wild

Cry, “Father put me in the boat.”

References

Knights, Arthur E. Notes by the Way in a Sailor’s Life.

The Loss of the Northfleet. Waterlow & Sons, London, 1873

Rockingham Bulletin, Queensland Australia, March 20, 1873

Brooklyn Daily Eagle

New York Times

Wellington Independent, April 23, 1873

Sydney Morning Herald, January 9, 1874

Loss of the ship Northfleet

The Loss of the Northfleet-ebook